"From pictorialism to Provoke: the most extensive history of Japanese photobooks ever published" Among others the over 500 pages counting book features such renowned photographers as Yoshio Watanabe, Akira Hoshi, Hayao Yoshikawa, Shinichi Kato, Yasuo Wakuda, Tetsuo Kitahara, Moriyama Daido, Koji Taki, Takuma Nakahira, Yutaka Takanashi, Kimura Ihei, Hamaya, Katura, Kazano, Kikuti, Mituzumi, Watanabe, Yamahata, Sozo Okada and Kazano Karuo, among many others. -- "'The Japanese Photobook, 1912–1980' illustrates the development of photography as seen in photo publications in Japan—from the time of influence by European and American pictorialism, the German Bauhaus and Imperial military propaganda, to the complete collapse and destruction of the country in 1945. Then followed a new beginning: with the unique self-determination of a young generation of photographers and visual artists highlighted by the “Provoke” style as well as protest and war documentation of the late 1950s to the early ’70s, the signature Japanese photobook, as we have come to know it, was born.

With detailed information and illustrations of over 400 photo publications, an introduction by Kaneko Ryuichi and essays by Fujimura Satomi, Duncan Forbes, Manfred Heiting, Mitsuda Yuri, Lizawa Kotaro, Shirayama Mari and Matthew S. Witkovsky, this is the first extensive English-language survey of Japanese photobooks of this period." (publisher's note)

About the main author:

Ryuichi Kaneko is a critic, historian, and collector of photobooks. He has authored or contributed to numerous publications, including 'Independent Photographers in Japan 1976–83' (Tokyo Shoseki, 1989), 'The History of Japanese Photography' (Yale University Press and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2003), 'Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and ’70s' (Aperture, 2009), and 'Japan’s Modern Divide' (J. Paul Getty Museum)

The story of Japanese photobooks, from 1912-1990

Written by Alex Jackson

From Sanrizuka photobook,1960s. The protest books erupted as a visual representation of widespread dissatisfaction across Japan. The protest books were a key form of artistic expression throughout the 1960s and 70s and incorporated the photograph into political struggles for representation. Included in The Japanese Photobook by Mafred Heiting and Kaneko Ryuichi, published by Steidl

The celebrated Japanese photobook in the 20th century - from the death of the Meiji Emperor to its anti-establishment heyday

Few countries have experienced as rapid a transformation as Japan during the 20th century. Once a closed country with extremely limited interaction with the outside world, it opened its borders to become a pioneer in many fields – including photobooks. Now a new compendium, The Japanese Photobook, 1912-1990, brings together some of the most important publications, a mammoth endeavour that took editor Manfred Heiting six years.

“It is in photobooks we saw the 20th century unfolding,” he says. “This is not a selection ‘best of’ or ‘the most valuable’ of photo books. It is intended to show the development of the Japanese photobooks and publishing, how it relates to the cultural development of the country, how it captured its most important historic events – and including all the book details – and differences in publishing.”

Together the photobooks depict how Japan adopted and adapted external influences into its daily life, but also the ongoing influence of Japanese culture. First used extensively by the military and brought into the public sphere with the photobook showing the funeral of the Meiji Emperor in 1912, Japanese photobooks have been a source of photographic inspiration around the world, particularly in the mid-20th century.

“Photography came late to Japan – and all ‘raw materials’ needed to be imported,” says Heiting. “When the few Japanese photographers and architects returned from studying at the Bauhaus, they brought those ideas home. These photographers adopted many ideas and started making some very interesting photobooks.”

As a key form of artistic expression in the region, Japanese photographers and publishers quickly used photobooks as a propaganda tool, and to document the changes in the country. When World War Two was over, the photobooks took on a different relevance as a means of social expression, depicting the mood and political situations in flux. An extended period of unrest provided fertile ground for young photographers to really experiment, while documenting what was going on in their country – particularly those involved with the Provoke magazine published on 1 November 1968, and 10 March and 10 August 1969.

“There was Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the American occupation, but also the uprising of students and farmers against the seizure of land for Narita Airport. It all unleashed the desire of the young generation to say that they had enough,” explains Heiting.

“The Provoke and protest publications are the most important Japanese contribution to photography and photobooks and photo magazines worldwide. The photobooks after the 1950s demonstrate a very unique Japanese identity to us.”

Unfortunately, Heiting sees the gradual demise of the artistic potential of the Japanese photobook starting with John Szarkowski’s exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1974. It was there that he told the show’s co-curator, Yamagishi Shoji, that “good photographs need to have a white border”. Ultimately, this led to a homogenisation: “That killed the uniqueness of Japanese photobooks. They all began to look like the ones in the West,” concludes Heiting.

The Japanese Photobook, 1912-1990, is published by Steidl, €125

Japan, just picture it

ByRobinon August 24, 2017

In 2015 Steidl published the remarkable (and visually stunning) 'Soviet photobook 1920-1941' edited by Manfred Heiting, the theme continues with this look at Japanese photobooks which he also edited. This survey considers 511 books starting with the funeral of the Meiji Emperor published in 1912 containing eighty-two photos by Ogawa Kazumasa. Before this printing techniques were still being developed and many books of photos existed as single unbound pages.

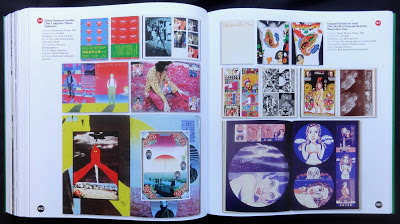

The book's twenty chapters examine Japanese photography as revealed in photobooks with a detailed look at specific historical highlights, for example: propaganda 1930-1944; the German influence; Leica camera 1937-1939; protest books 1960-1978; underground 1968-1978. The chapter on Manchukuo 1932-1942 (after 1945 Manchuria) has some fascinating picture books showing new development with buildings, industry and agriculture which Japan hoped, with overseas distribution, would be the fastest way for international recognition for the country they invaded.

Japan and Germany signed an Anti-Comintern Pact in 1936 (essentially to contain the Soviet Union) and this produced a rather intriguing collection of photobooks about the 1936 Olympic Games, Bauhaus design, the small hand-held Leica (ten books fare eatured) and of course WW2. The Japanese military produced a visually exciting propaganda magazine called 'Front' (with design inspiration from the famous 'USSR in construction') there are forty spreads in the book showing an amazing use of photos and design. Page 228 shows Hitler's 'Mein kampf' published in Japanese with photos by Heinrich Hoffmann (which were absent from the German edition).

An unusual chapter 'The photocopy photobook' shows several 'books' of photos run-off in the seventies from Araki Nobuyoshi and others using lightweight CH paper with stapled sheets and in short editions that exploited the reduced grey tones of the Xerox copiers. The longest chapter, over seventy-three pages, looks at photobook series from 1909 to 1982, this seems an area of publishing that is almost unique to Japan with books published as a visual record of the countries culture and development over the decades. There are three chapters without a specific title other than 'Book selection' 1945-1959, 1960-1975 and 1976-1990. It's a chance to display the cover and inside spreads from a choice of worthwhile photo titles.

As with the Soviet photobook I mentioned this Japanese edition is a handsome looking production, the 3500 covers and spreads all have a slight drop shadow with printing using a 175 screen. Despite the huge number of illustrations they are all very legible and nicely lots of the titles get a very generous helping of pages so the reader can get a feel of the book, for example: 'Japan: the nation in panorama' has the color cover and thirty-three spreads.

From Kamera to kikansha photobook, 1938. This was part of an avant-garde photography movement in the 1920s and 30s, influenced by European photography. Here, the photobook explores some of the new technologies of the age introduced to Japan. Included in The Japanese Photobook by Manfred Heiting and Kaneko Ryuichi, published by Steidl

From Front photobook, 1942-43. The Japanese military were the first to see the potential of photography back in the late 19th century and used it continually ever since. They found it to be an effective method of propaganda during the war years. Included in The Japanese Photobook by Manfred Heiting and Kaneko Ryuichi, published by Steidl

From Front, Immortal Hind and Idainaru Kensetsu: Manshukoku photobooks, 1943-44. The Japanese military were the first to see the potential of photography back in the late 19th century and used it continually ever since. They found it to be an effective method of propaganda during the war years. Included in The Japanese Photobook by Manfred Heiting and Kaneko Ryuichi, published by Steidl

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten